Historical Truth & Poetic Truth

Elementary school foundations, Cornwall Bridge, CT

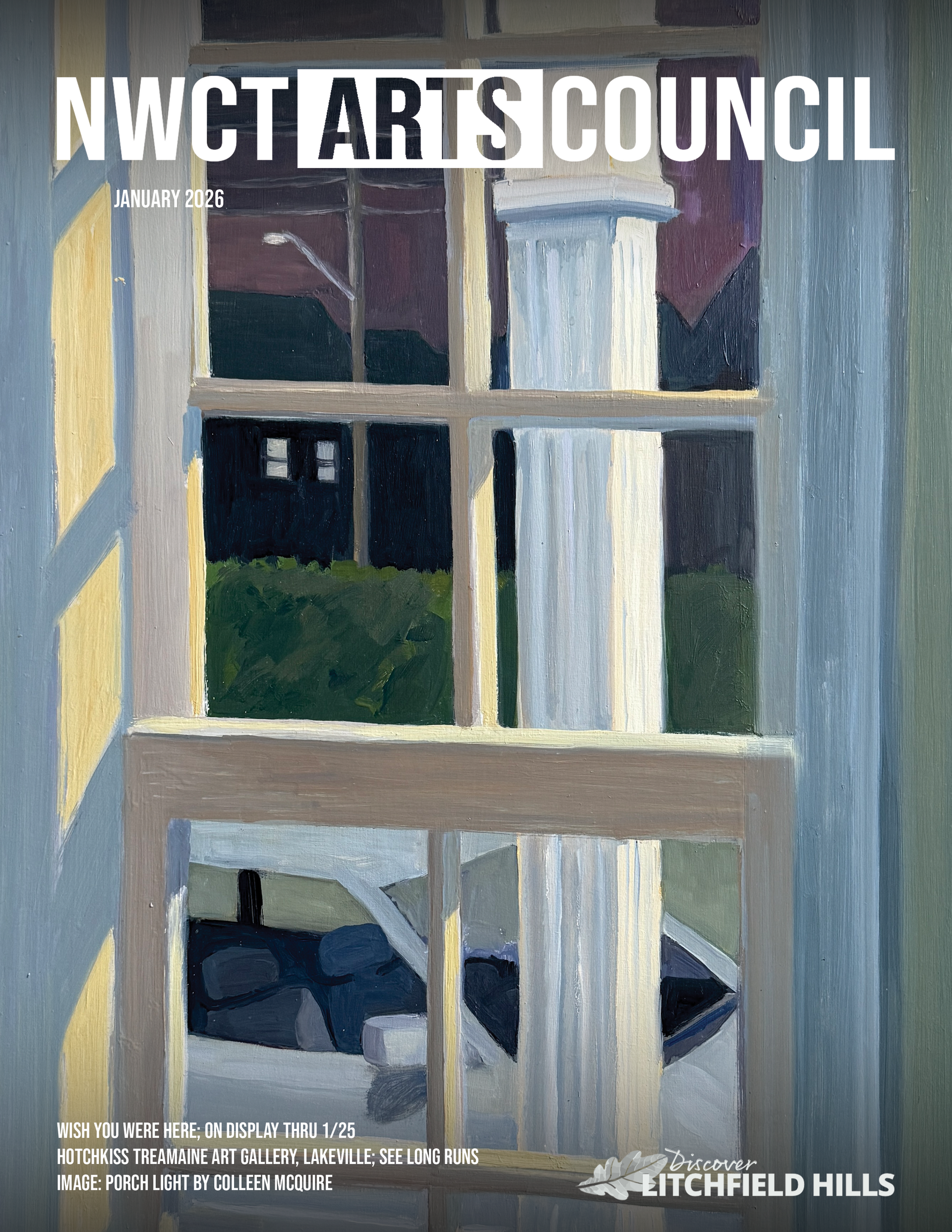

Examining traces of the past found in the landscape offers a chance to think about the relationship of the world to both historical truth and poetic truth. Pictured above are the foundations of an old elementary school in Cornwall Bridge, with a stonewall traversing the slope behind it. In the early American republic, communities built many schools -- primarily to foster literacy for faith and for democracy. The solid granite of both stone wall and sills reminds us of how local materials largely determine how the built environment looks. The huge boulder protruding from the center of the square foundation must have broken through the floor -- I imagine it as a throne for those unruly students condemned to the dunce corner. No doubt the oak scholar benches were cut from these very forests.

These concrete aspects underpin some more abstract truths. Education functioned as a cornerstone of ideas about representative democracy: the model pioneered in early America weaponized the insight that persuading people works much better than forcing them. If a society can instill ideas in the minds of children, shared assumptions create a stable mentality, less inclined to disruptive questions and dissident behaviors. Loyalty to nation is imbibed with the ABCs, making the Republic of Letters a patriotic project. (See Patricia Crain The Story of A: The Alphabetization of America from The New England Primer to The Scarlet Letter).

John Ridge, Cornwall educated, later a

Cherokee leader who reluctantly led his people

on Trail of Tears exodus from Georgia

In the microcosm of this small town in northwest Connecticut, this push to literacy connected with self-rule through town meetings, but also to another nearby educational experiment, the Foreign Mission School established by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, aimed at educating non-Christians. Chinese students came here, but also such Native Americans as John Ridge of the Cherokee. (See John Demos' wonderful analysis in The Heathen School: A Story of Hope and Betrayal in the Early Republic.) This multicultural mix reminds us that the "civilizing mission" encompassed early American global commercial impulses, as well as the dispossession and obliteration of domestic Native Americans. And yet the Schaghticoke still live on the banks of the Housatonic River.

Even in this tiny town, ideas about literacy, Christian duty, democracy, and politics jostled against ideas about commerce, capitalism, imperial power and domination. You might say, those stone foundations still speak loudly today. Perhaps, you could call landscape history a form of free speech, if heard in the right way. Lost trails, lost forests, lost buildings, lost people -- distant but still audible.

Housatonic RR tracks separate school and river

Reading the landscape from a different angle, we can hear the moccasined tread of the area's native inhabitants, the Munsee-Lenape, Mohican, Tunxis, Wappingers, Paugussett, Pequonnock, and today's Schaghticoke. The spirits of deer, black bear and rabbit cavort amid the maples and oaks descended from those days. The kinship of animate and inanimate is palpable: doe and granite, cub and sapling nourish the energy envelope of the school, situated 100 feet from the Housatonic River. The handmade stone wall evokes the feel of daily life for European settlers, just as much as the little schoolhouse summons images of bundled children trudging through snow drifts to school. Even the railroad tracks map a layer of the palimpsest of the past, a shimmer of memory that embraces nature and culture. So, historical truth and poetic truth coexist, touching both the material and ethereal worlds.

Article originally posted at

https://ramblingdigitalhumanist.blogspot.com/2021/11/historical-truth-poetic-truth.html.